Getty Images

Twenty years ago, something truly unbelievable happened.

The Boston Red Sox, a self-described “band of idiots,” broke an 86-year curse, and won the World Series.

It hadn’t happened in my father’s lifetime, or my grandfather’s lifetime.

There were times I didn’t think it would happen in my lifetime.

This is the first in a series of articles about the people who made this miracle happen.

Not necessarily in order of importance. In chronological order. In whatever order makes sense to me.

I’ll try to publish one article each week of this 2024 season.

And just remember: Every single word of this is true.

January 14, 2004: Boston MA

It was a frigid New England night, with a cruel wind whipping down Commonwealth Avenue.

Only the heartiest of souls braved the sub-zero wind chill to seek the shelter of the Paradise Rock Club in Brighton.

Inside, we took off our coats, and took comfort in the company of fellow believers, gathered for a night of “Hot Stove, Cool Music”.

It was the creation of former Boston Globe baseball writer Peter Gammons (with ESPN at that point), with the help of his friend Jeff Horrigan (baseball writer for the Boston Herald).

The night combined three of Boston’s passions: baseball, music, and the Jimmy Fund.

This was the fourth “Hot Stove, Cool Music” night since its inception in December 2000.

It raised $17,000 for the Jimmy Fund on its first night. Since then it’s raised more than $16 million.

Red Sox General Manager Theo Epstein expanded it to Chicago when he moved to the Cubs in 2012, and it has added other charitable organizations.

But in January 2004, it was all about Boston.

We were licking our wounds, after our gut-punch loss to the hated Yankees in the 2003 American League Championship Series.

In Game 7, six outs away from the World Series, Grady Little had left an exhausted Pedro Martinez in too long, and a three-run lead had vanished in a heartbeat.

Tim Wakefield had pitched valiantly into the 11th inning.

But Aaron Boone hit the first pitch of the inning into the stands, sending the Yankees to the World Series, the Bronx into a frenzy, and Red Sox fans into another winter of despair.

But three months later, on a cold night in January, we still found a reason to believe.

The front room of the Paradise was filled with silent auction items for the Jimmy Fund – people were bidding on a signed bat or a ball, lunch with a Red Sox player, or a night in one of the Fenway sky boxes.

It was a cozy enough gathering that I happened to bump into Peter Gammons, and I thanked him for putting on the event.

It was personal – my father had recently succumbed to cancer.

It was personal for a lot of us.

The Jimmy Fund was the fund-raising arm of the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, a world-class hospital.

People from all over the world, people who had been drained of all hope, came to Boston in hopes of finding a cure.

Any New England kid had stories of raising money for the Jimmy Fund – it was the official charity of the Red Sox.

And we all had stories of loved ones who had battled cancer. Many survived, thanks to Dana Farber and the Jimmy Fund.

(The Red Sox have since welcomed several other charities.)

As I made my way to the main room of the Paradise, The Gentlemen (a local rock band fronted by Mike Gent) were onstage, kicking things off with their fun, raucous anthem, “Sour Mash”.

The Georgia Satellites had nothing on these guys.

Seriously, how many songs have an opening couplet like this?

I met her in the summer of my sorrow/She was high-heel deep in a bottle of sour mash

I asked her for a beer I could borrow/She looked like June, and talked like Johnny Cash

We were in for a good night.

The three things I believe in most (other than my daughters) are: good writing, good music, and baseball.

I fell in love with all three, in good part because of Peter Gammons.

I wasn’t alone.

A whole generation of sabermetric kids, led by Theo Epstein, were raised on Gammons’s “Sunday Baseball Notes” in the Boston Globe.

If you took a poll of the GMs in today’s game, you’d find that most of them grew up reading Peter’s Sunday notes column. Just like Theo did.

Nowadays, every publication has a weekly “Notes” column, for every sport.

We take them for granted, like they existed forever.

They didn’t – Gammons invented them.

They were alive, and fun, and full of the colorful characters of the game.

Not just the stars, but the personalities, guys like Micky Hatcher, Oil Can Boyd, and Darin Erstad.

Here’s how respected Peter was – how revered he was: All-star righty Jack Morris – who pitched the Twins, Tigers, and Blue Jays to World Series championships – finally said out loud what everybody knew, and called him “The Commissioner”.

He might as well have been.

GMs would call him, to see what trades other teams were thinking about.

Why was Peter so revered? Sure, he had connections across the game.

Yeah, he knew the game, as well as the Cape Cod League scouts that he befriended and relied upon.

But mainly – Peter Gammons is just an exceptional human being.

His Hall of Fame speech, when he was inducted in August 2005 (the Ford Frick Award for great baseball writing) is a thing of beauty and humility.

“Throughout my career I have tried to be guided by one principle,” he said. “That because I am human, I have the right to like people. But because I am professional, I have no right to dislike anyone.”

That principle has guided him since he started with the Globe in 1969, and led him to many good friends across generations of ballplayers, managers, and GMs.

* * *

If you grew up in Boston in the ’60s, as Peter did, you were lucky.

We grew up in an explosion of music.

We had great radio stations – WRKO, playing Top 40 with a local twist in the ‘60s, WBCN, playing crazy, ground-breaking stuff in the ‘70s, WFNX playing alternative rock in the ‘80s.

Boston DJs were breaking songs before they were heard anywhere else.

We had streets full of incredible nightclubs and bars – The Tea Party, Jonathan Swift’s, Jack’s Bar, Johnny D’s… You could hear great music, any night of the week, often without a cover charge.

Sure, we cranked out a slew of nationally-known bands – Aerosmith, The Cars, Boston, The J. Geils Band …

But we had an army of local hero bands: Jonathan Richman & the Modern Lovers, Barry & the Remains, The Neighborhoods, The Lyres, The Del Fuegos….

Maybe I was biased – but even as a kid, I felt like Boston was a special place.

Peter was as passionate about music as he was about baseball.

He happily worked his latest faves into the Sunday Notes columns.

Thanks to Peter, I grew to know Bonnie Raitt, Richard Thompson, John Hiatt, the Gin Blossoms, Ryan Adams…

All these people, I learned about from Peter Gammons.

Peter was an early proponent of bands like Pearl Jam, and became friends with them and several other bands, like local gal Susan Tedeschi (and her husband/musical partner, Derek Trucks).

Same with Paul Barrere of Little Feat (his personal icons).

One of those friends was Kay Hanley, the lead singer of Letters to Cleo.

A good Dorchester gal, Kay worshipped Peter – and he in turn loved her maniacal passion for the Red Sox.

How big a baseball fan was she?

When Kay and her husband (guitarist Michael Eisenstein) had their first child, they named him after Henry Aaron.

How maniacal was she?

On Letters to Cleo tours, Kay and Michael would take in ballgames along the way.

When they stopped in Cincinnati, Reds coach Ray Knight offered to take a picture with them.

But Kay refused: She knew damn well that Knight had scored the winning run for the Mets in Game 6 of the 1986 World Series; there was no way she was gonna be in a photo with him.

Kay was a fixture of “Hot Stove/ Cool Music” from the very beginning, and she played and helped organize every year.

She was mingling with the crowd before the show, so I stopped and said hello to her, too.

I told her of my pre-teen daughters’ obsession with Kay’s songs for the Josie and the Pussycats soundtrack. She laughed and signed a napkin for them: “Josie 4Eva!!”

It’s hard to understand now, here in this city of champions.

Twenty years later, we’re spoiled. Entitled.

But back then, the Boston sports scene was a wasteland.

It was Loserville.

Back in 2001, our last championship had been won by the Celtics, in 1986.

The Bruins had last won the Stanley Cup in 1972.

The Patriots had never won. Until 2002, when they shocked the world and won the Super Bowl. And everything changed.

The Red Sox? You might’ve heard… 1918.

Growing up in New England you learned to recite the litany of heartache that the Red Sox forced us to endure.

There was:

- Enos Slaughter, scampering all the way around from first base – on a single – to beat the Red Sox in the 1946 World Series

- Manager Joe McCarty inexplicably starting journeyman Denny Galehouse in the 1948 playoff which we lost to the Cleveland Indians

- Starting Jim Lonborg on two days rest in the 1967 World Series, and losing to Bob Gibson and the St. Louis Cardinals

- Luis Aparicio tripping around third base, and killing a rally in 1972, allowing the Tigers to win the AL pennant

- Bill Lee throwing his “eephus” pitch to Tony Perez (ignoring all instructions) and losing the 1975 World Series to the Reds

- Bucky Fucking Dent hitting a pop fly that somehow carried into the screen above The Monster, and winning the 1978 Playoff Game for the Yankees, after we blew a 13-1/2 game lead in August

Then there was 1986.

When the Red Sox scored two runs in the 10th inning of Game 6, parents actually got their young children out of bed, so that they could witness something that had never happened in their lifetime – the Red Sox winning a World Series.

(I actually knew several of these parents, and love them dearly for it.)

Unfortunately, what their groggy children got to witness was the baseball version of a horror movie – after getting the first two outs, and then getting two strikes on the final batter, Calvin Schiraldi gave up four hits in a row. The Mets won the game, and the next night they won the World Series.

(We will entertain no talk of Bill Buckner. It was not his fault.)

In a way, it was perfect that those parents woke their children up from their dreams – they got to witness the very same heartache that their parents had grown up with.

As a drunken patron at a Boston bar moaned when we lost the 1978 playoff game, “Those sons of bitches killed our fathers, and now they’re coming for us!”

Kids in other places learned the Pledge of Allegiance.

In New England we learned the Curse of the Bambino.

(Those of you from New England, please forgive the following. You know the story already.)

After the Red Sox won the World Series in 1918, their owner, Harry Frazee, was trying to finance his latest Broadway production, No No Nanette.

Short on cash, he decided to sell his bright young star. A kid named Babe Ruth. Nicknamed The Bambino.

For $100,000, No No Nanette got its backing. And the New York Yankees got the most iconic slugger (and character) the game ever had.

And the Red Sox never won the World Series again.

As Bill Lee, the free-spirited left-hander who gave up the Eephus homer to Tony Perez, eloquently put it, “They sent Babe Ruth away to New York, where he became an alcoholic, and the team was cursed. It was the Curse of the Bambino.”

Globe sportswriter Dan Shaughnessy took it and ran with it. He wrote a successful book of that name, and created a cottage industry of “The Curse of the Bambino.”

But Peter Gammons didn’t believe in curses.

“There was never a curse,” he said. “The only curse of the Red Sox was poor ownership and poor management, along with racism and alcoholism.”

* * *

Peter Gammons was onstage now at the Paradise, with his sidekick Kay Hanley.

They were doing a Q&A session before the next act, Kay reading questions from cards submitted by audience members, Peter answering thoughtfully.

Kay picked out one card, with an evil, gleeful gleam in her eye.

“Why do the Yankees suck so bad?” she read .

Right on cue, a chant of “Yankees suck!” broke out, until Peter calmed them down.

They then brought up one of their guests of honor: Theo Epstein, Red Sox General Manager.

Except tonight, he was Theo Epstein, rhythm guitarist for the alternative rock band, Trauser.(You could tell they were “alternative” by the German spelling of “trauser.”)

Theo was in full rock star mode, looking like The Edge, in a flannel shirt and wool cap.

The mutual admiration between Peter and Theo was obvious, as Peter asked the young GM some baseball questions before they played.

Peter read a fan’s question: “What’s it like, running the Red Sox?”

Theo paused, then sneered. “Ask Lucchino.” He had the full rock star attitude with him, too.

The crowd howled, delighted at the shade he was throwing his boss, Red Sox partner and President of Baseball Operations, Larry Lucchino.

Then Theo slung the guitar over his shoulder and Trauser launched into Neil Young’s “Rockin’ in the Free World.”

Something different is happening here, I thought.

As Lucchino had said when he hired 28-year-old Theo: “This is not your father’s Red Sox.”

* * *

Finally, it was time for the main attraction.

Peter took the stage, this time with a guitar, backed by his Hot Stove Cool Music All-Stars.

He had started playing in high school with his band: The… ahem… Fabulous Penetrations.

“We almost didn’t graduate because of that,” he told reporter Tom Friend.

(If you do nothing else, read Friend’s extraordinary, gratifying story about Gammons. Tom does a better job than I ever could of demonstrating why Peter is such a unique human being. He also tells about Peter’s own miracle in 2006, how a retired nurse found him in the back seat of his Lexus in a Mashpee MA parking lot, passed out with a brain aneurysm, and how her actions, and the actions of others saved his life. It may be the best appreciation of anybody I’ve ever read.)

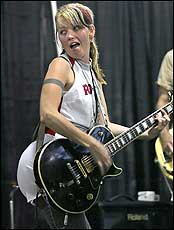

As the band plugged in, young women squeezed up to the front of the stage.

Peter launched into a recognizable Chuck Berry lead, and he howled, “Well the joint was rocking, going ‘round and ‘round.”

The Paradise erupted.

Young women in front of the stage screamed.

The wise guys in front of me roared with laughter. “Gammons has groupies!”

Something’s happening here.

The odd thing is, Boston is a small market. It’s not even close in size to New York, LA, Chicago, Houston…

So why are the Red Sox known as a big-market team?

Because of our ferocious faith. Because of our manic, blind, illogical, unrequited, misplaced, totally unjustified faith.

Because we pack 35,000 people into Fenway Park, every night.

Because we tune in to New England Sports Network (NESN) at levels that other franchises salivate over. Even now, we fork over money for outdated cable TV, just so we can catch our Red Sox games.

Because we huddle together on cold January nights, to catch our “Hot Stove, Cool Music” shows.

I remember coming home from college in Chicago (in 1980), and it suddenly struck me just how many Red Sox hats you’d see.

You don’t see that anywhere else.

People in San Diego might throw on a Padres hat – but mainly as a fashion choice.

People in Houston might pick out an Astros hat – because they’re in the playoffs.

People in Atlanta might throw on a Braves hat – but their grandfather didn’t wear one.

Here in Boston, it’s not a sartorial choice – it’s a birthright.

It’s a statement of faith.

* * *

On that cold January night in 2004, several Red Sox players took part in the festivities.

AL batting champ Bill Mueller chatted with fans.

Bronson Arroyo, with his own guitar and a budding musical career, played a few songs.

Kevin Millar took the stage and whipped the crowd into a frenzy with all of his goofy Kevin Millar-ness.

New manager Terry Francona took in the scene from the side of stage, with a bemused smile.

And you could tell – they got it.

This wasn’t San Francisco, or Pittsburgh, or Philly.

This was different.

Something was different.

Something was happening.

The night wrapped up, and we threw back on our coats, and marched back into the street.

But despite the cold and the wind, we were warm, full of companionship, pride, and hope.

We had so many good people on our side. How could we go wrong?

We had a brilliant young GM, one of the Sons of Gammons, running our ship. How could we fail?

We had devil-may-care instigator Kevin Millar, whipping the crowd into a frenzy., getting us to believe, Why not us?

We weren’t cursed. We were blessed.

One thought on “The Miracle of 2004: Peter Gammons”