When did I fall in love with Reservation Dogs?

It might’ve been the first episode, when I realized one of the Indian kids is named Elora Danan – after the lost baby in the 1988 fantasy movie, Willow.

It becomes a running gag throughout the series, with characters recognizing her name, and reminiscing fondly about the Ron Howard movie (now lovingly brought back to life as a Disney+ series).

Maybe it was the fifth episode, “Come And Get Your Love”.

True to its title, it is built around the 1974 Top Ten hit by the Native American band, Redbone.

By the time the episode ended with a video of Redbone performing the song, I knew I was along for the ride.

Probably it was the first episode of Season Two, when the ghost of Tom Petty is invoked to break a curse.

Two elders are squabbling over the best way to break an errant spell cast by one of the Rez Dawgs. The elders decide that they need to sing a song. “An old song!” they agree.

So they break enthusiastically into “Free Falling”, incanting, “She’s a good girl, loves her mother,” as they float the cursed hair of the victim down the river, before arguing over the lyrics.

(In spite of everything, Petty’s song works, and the spell is broken.)

Shane Brown/FX

Yeah, Reservation Dogs (on FX and Hulu) is a show about Native American kids.

Sure enough, it shows you a picture of life on the reservation, and just how things are stacked against them.

Yet, it’s realistic, without being melodramatic.

Yeah, the IHS (Indian Health System) is a mess. Most kids don’t have a mom and a dad at home. Money is hard to come by. Suicide (and other death) is everywhere.

That’s just life on The Rez.

So why do you end up laughing so much?

Shane Brown/FX

“Most of the time people are very precious with Native American people, and ‘This is no laughing matter,’” show creator Sterlin Harjo tells Terry Gross (in a really fun, joyful Fresh Air interview).

Mr. Harjo explains “That’s kind of how the world is trained to view us. And we realized that we needed to ‘beg in’ on this show, for permission to laugh with us.”

No matter how many people I’ve told about the show, I always stumble over the name, wanting to call it Reservoir Dogs.

That’s intentional, Harjo says.

That 1992 Quentin Tarantino film was what made him want to make movies, he tells Terry Gross. (He also tells Terry, he used to day-dream about appearing on her show; as a young film-maker, that’s how he’d know he’d ‘made it.’)

Harjo’s love for Tarantino oozes out, through the constant pop culture references, the running gags, and the quirky characters.

To be fair, Harjo’s characters have a little more heart, though.

You find yourself caring – achingly – for them.

The four main characters – all high school kids, or recently out – are the main reason to watch Reservation Dogs.

They’re cocky, but unsure of themselves.

They stick together like glue, but they’re driven by their own teen angst.

Mostly, they’re funny as hell.

Bear (played by D’Pharoah Woon-A-Tai), is their self-proclaimed leader.

With his high cheekbones, long hair, and soulful, eyes, he plays like a Native James Dean.

But he’s just as confused than any of them. He wants desperately to idolize his rap-star dad, but he’s a dead-beat, a habitual no-show in his life.

When Bear gets beat up by a rival gang, he moans, “Man, it’s hard being a leader of a gang… You’re always a target.”

His pals burst out laughing. “You think you’re the leader? Really?”

Elora (K. Devery Jacobs, who also writes some of the episodes), is really their driving force, leading them toward their trip to California, and organizing their raids to steal money, to get off The Rez.

But my favorites are Willie Jack (Paulina Alexis) and Cheese (Lane Factor).

Cheese (somehow short for Chester) is the youngest – but he’s the conscience of the group.

He’s the one the gang calls on to lead them in prayer.

As he says, with a shrug, he just tries to treat people like he would like to be treated.

He always introduces himself, “My name is Cheese. My pronouns are he, him, and his.”

When a confused character responds, “What, are you gay?” Cheese looks quizzically and patiently explains, “You realize that gender identity and sexual orientation are two different things, right?”

As Mr. Harjo says of the character he created, “He’s just showing that it’s not that difficult to be nice to people.”

Willie Jack (short for Wilhelmina Jacqueline) is another youthful sage, tossing out truth-bombs (or zingers) with her sing-songy, childlike voice.

On the morning of her parents’ anniversary, she covertly slips her dad a gift card from a local restaurant. “You stole this, didn’t you?” he whispers.

She nods, and then nudges him: “Dad, did you give Mom her anniversary present yet?”

Mom is impressed by his largesse. “Fifty dollars, huh?”

Dad leans back and smiles, sipping his coffee. “You’re worth it, babe.”

Give yourself five minutes and watch the scene above. It’s from the next-to-the-last episode of Season Two.

It shows how Willie Jack is the soul of the Rez Dawgs, and the soul of the show itself.

It’s perhaps the central scene from the whole series.

If there’s a more moving scene from any show last year, I’d like to see it.

The background: The death of their friend Daniel has torn into the Rez Dawgs. In ways they can’t voice, in ways they can’t repair.

Bear and Elora don’t talk. Cheese just hangs out with his adopted grandmother.

Willie Jack can’t stand to watch her friends fall apart. She sees herself as a caretaker, a wizard, but she’s hopeless to help her friends as they fall “into the darkness”.

In desperation, she visits Daniel’s mother, Hotki, in prison. She, just like the kids, fell apart after Daniel’s death.

Hotki used to be a leader to the kids, a healer, a role model to Willie Jack. Now she’s just hardened stone, bitterly doing time.

Before the visit, Hotki is visited by a spirit, encouraging her to pull herself up and remember who she is. (You’ll see her off to the side in this scene, in the blue dress, before moving directly behind Willie Jack .)

Willie Jack begs for help, and Hotki finally softens up – after coercing an offering of chips and energy drinks from Willie Jack.

After the downing of the drinks, and a satisfied belching, something amazing happens.

The camera slowly zooms in, and we’re suddenly seeing things from Willie Jack’s perspective, instead of the side angle.

Hotki’s eyes soften, as she tells her young niece to put her hands on the table, palms up.

And she begins to pray.

You see every bit of Harjo’s incredible direction, as Willie Jack appears alone, as if no one else is in the room.

You see the incredible actress that young Paulina Alexis is.

You see her transform from cocky spitfire, to vulnerable kid, to scared rabbit, to sobbing with realization, as she is literally touched by the spirits.

You see her hide her tears in her t-shirt and her curses, feeling the power within her.

You should probably watch the last two episodes of Season Two together. (In half-hour nuggets, it’s pretty easy.)

After her visit with Hotki, Willie Jack rebuilds the Rez Dawgs, and brings them together for their Cali trip, as their lost friend Daniel wanted.

If you can watch the final scene without breaking down into tears, you’re a stronger human than me.

Shane Brown/FX

Reservation Dogs has been renewed for a third season.

Word is, they hope to have it ready in 2023.

It is just the latest in the growing legacy of FX/Hulu shows (Atlanta, Justified, The Bear).

It’ll remind you of Atlanta, both shows telling the story of an unseen minority group.

It shares a lot of surrealism of that great Donald Glover show: ancestral spirits visit the youngsters, mythical creatures pass through, and past events are shown in black & white flashbacks (in varying perspectives, depending on who’s telling the story).

If it reminds you of Taika Waititi’s movies, too, there’s good reason for that.

Waititi is co-creator, and he helped Sterlin Harjo bring his vision to life.

(A character in Reservation Dogs meets a demise similar to a main character in JoJo Rabbit. It’s just as shocking, as they’re found by a loved one.)

Shane Brown/FX

There tend to be three constants in a lot of my favorite TV shows: good music, quirky characters, and friendship.

Reservation Dogs has all three, in spades.

Quirky characters are in abundance.

There’s Mose and Meeko, two small-sized rappers (played by real life Native rappers Lil’ Mike and Funnybone). They provide, alternately, comic relief and a Greek chorus, as they peddle around The Rez on their bicycles.

There’s Officer Big, the stoic, kind-hearted tribal policeman who hides a happy, goofy soul behind his badge and uniform.

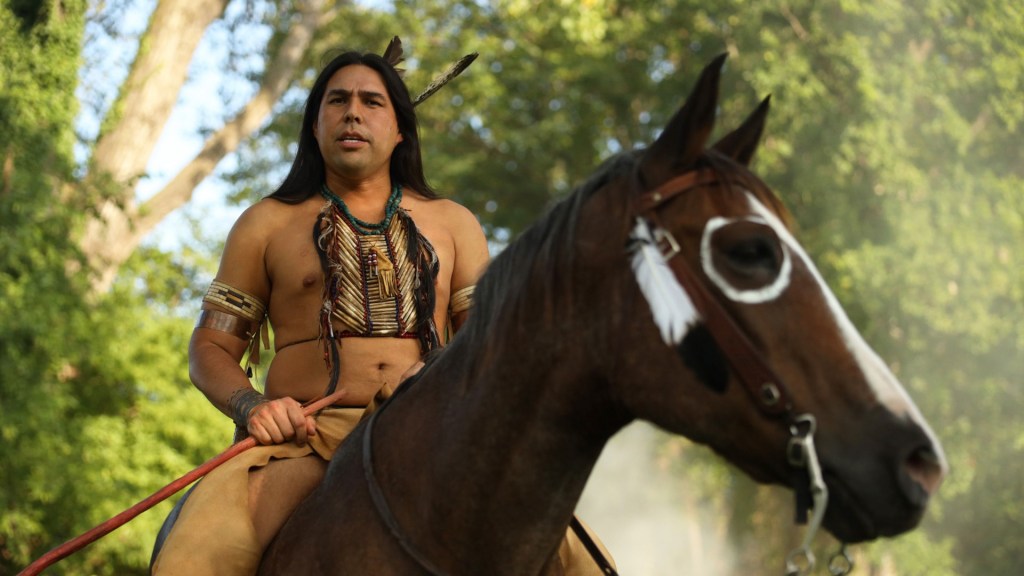

There’s the anonymous “Spirit”, an ancient warrior who comes down from above to guide Bear. He offers foul-mouthed (but worldly) advice while sitting in the porta potty, or while eating communion wafers that he steals from the church. (”Body of Christ?” he asks, as he offers one.)

The music jumps out, right from the opening scene, where Iggy & the Stooges’ “I Wanna Be Your Dog” accompanies the Rez Dawgs’ hectic, half-assed heist of a food truck.

From there, it flows with rootsy people like Link Wray, Doug Sahm, Loudon Wainwright III, JD McPherson, Sturgill Simpson, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Cypress Hill, Wanda Jackson, Leon Russell, and the Turnpike Troubadours. And Cyndi Lauper, for good measure.

The songs are all fun, quirky, thoughtful, and authentic. Just like the characters in the show.

Reservation Dogs prides itself on being the only show entirely made of Native American actors and writers.

It’s filmed on site in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, where Sterlin Harjo (of Seminole and Muskogee heritage) grew up.

After watching the show, his dad proudly told Sterlin, “You made us feel seen now.”

As Harjo told Terry Gross, “That meant more than any Emmy nomination, or any award ever could.”

At its soul, it is about being Native American. Or Indian. (As Harjo said, “I’m used to ‘Indian’. My grandmother said ‘Indian’. I’m sorry that Christopher Columbus got it wrong. But that’s what we call ourselves.”)

But more than anything, it’s a show about friendship.

About being there for each other. About standing up for each other.

Which makes it, really, about each and every one of us.